escalator over the hill

dhalgren, samuel r. delany's epic novel of smoke and mirrors; the utopian underwater techno of drexciya; the world-building and -rebuilding of the anime series revolutionary girl utena

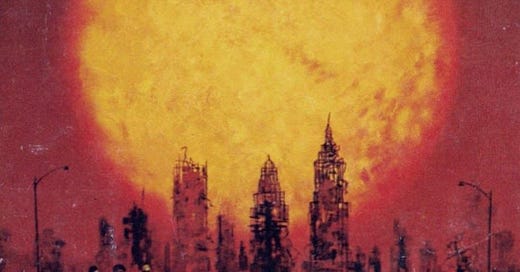

1 dhalgren (1975, samuel r. delany). the seasons appear to have stopped. the sky is one continuous smoke cloud, and the air feels hot and close year-round. (grey) day still deepens into (grey) night, but time doesn’t make any meaningful progress. newspapers are issued daily by the city’s self-selected mayor, but the dates on the covers are out of sequence, occurring in the remote past or future, and none of the inhabitants have a grasp on exactly when the present moment is either. this is bellona, the invented american city where samuel delany’s novel dhalgren takes place. it’s a city that’s been loosened from the web of history, torn from its original context. time is stopped there; it flows around it, not through, like a river split at its rim.

the appearance of bellona is a reflection of the sky overhead: a gnarled grey husk, whole blocks of it filled with the black grins of broken windows, empty shopping malls like hives of echoes, long chains swaying in the total absence of wind. some cataclysmic event—which, even as we learn more about it, never really comes into focus, surviving only as fragments of sound and image in the population’s memory (riots, fires, sirens, screaming, glass)—rippled through the city, and ever since bellona has lived in the shadow of its own apocalypse. fires burn constantly behind the windows of buildings on the smudged horizon. the buildings themselves are apparitional, rooms and hallways within them disappearing and reappearing, ghosts of a lost structure. the layout of streets seems to shift depending on the day, and nothing is ever quite where you remembered it, as if the whole city had just turned on an axis. there is almost no power, though certain parts of the electrical grid still flicker like they’re struggling to remember themselves. but most of the time the dark is only broken up by giant animal skeletons made of light, emitted from the optic chains worn by a roaming street gang called the scorpions.

it seems like it must be impossible to live in bellona, but people manage to stay there for months and even years, existing by only the meagerest of means and carving out a dignified life for themselves, depending on one’s definition of dignity, which is often dependent on context. there is no industry; a delusional patriarch still pantomimes going to work every day even though whatever job he used to perform has completely evaporated from the city. there is a bar, but all of the beer is free, because there’s almost no money in bellona, and what little there is to be had is worthless. there are no cops, and thus there is no “crime”—people subsist on whatever food they can take from abandoned markets and no one can prevent them from attempting to survive. (in the absence of cops, however, a group of concerned white citizens has formed a militia which patrols the upper levels of the mall with sniper rifles.) the scorpions are an unruly crowd of burnouts with anger management issues, but their capacity for violence, with a few exceptions, is a performance. in fact, almost all of the action in dhalgren is death, and almost all of the death is gruesomely accidental, even though each accident also has a shadow of intent looming beneath it, cause and effect getting murkier and murkier as people get more and more displaced from their desires. one character falls down an elevator shaft—or was potentially pushed down the elevator shaft by his sister after he threatened to show their (white) parents a poster she had of a naked black man—and the scene where the main character wades through a red sea of grotesque description to retrieve the brother’s mostly liquid corpse is among the most memorable and eventful in the book.

i say “eventful” because otherwise not a lot happens in dhalgren. it can be reductively described as a series of conversations; the main character—who doesn’t have a real name, or at least can’t remember it, but is referred to as “the kid” or “kid” or kidd” by other characters throughout the text—drifts from gathering to gathering, from hippie enclaves to nuclear families to, finally, the barely-controlled chaos of the scorpions, trying to reassemble who he is from the reflections or refractions of self that others emit or desperately try to disguise. depending on his surroundings, the person he is literally changes, down to the articulation of his name, and at different points in the novel he finds himself referred to as a poet, or a hero, or the leader of a gang, even though he struggles to feel any specific identification with these categories. relating to a text is not a priority for me in enjoying it, otherwise i would read a lot of very boring books, but it was kid’s amnesiac sense of self, a wave that is always collapsing at his every attempt to grasp it, that kept resonating with me over the five months i spent wading through this very, very long novel. it reminded me of the blankness i feel every morning just a few seconds after waking up, before the personality i went to sleep with reasserts itself, when my mind is just a gap in space.

the other thing that happens in dhalgren is sex, practically an unstemmed tide of it, starting from the very first scene and culminating in a gangbang so mindless and endless it starts to have a hallucinatory effect on the participants and the reader, rapturous moans echoing off the humid walls of a dream room. the ease and frequency of sex in the novel actually reminds me more of conversations than almost any real-life sex i’ve had—characters melt into it almost absently, drowsily, realizing only minutes later in how immersed they are in the other person, in the very matrix of feelings and impulses that produces their personality. (in the novel, as in real life, i think, sex is just another form of understanding someone and reflecting that understanding back at them.)

this overflow of sex is taken directly from delany’s experience; for several months in the late 1960s, delany roomed with the members of his band (whose music, even after reading about it, i could not describe to you, except that it seemed both rooted in folk and subject to proggy excess; in my head this sounds like the moody blues, but we can’t know for sure because they never recorded a note) and a rotating cast of 10-20 others in a commune that took up the first floor of a lower east side apartment building; they lived so closely that sex was a subgenre of their interactions, and became yet another form of caring for one other. delany recounts this time in his life in the memoir heavenly breakfast, named after the band and commune; i read it right after dhalgren, and it sort of acts as an appendix of reality for the novel’s more ambiguous fictions. the scorpions even appear in the memoir as a group of unsavory characters that delany encounters in an apartment building a few blocks from the heavenly breakfast. wrapped in leather vests and silver chains, vigorously offering to eliminate any snitches that delany or his friends know of, their walls decorated with handcuffs and leather pieces hanging from nails driven into the wall, they embodied the part of commune life that delany wanted most to embed in dhalgren—that intimacy and community could be found among the most unexpected and seemingly-distorted characters, in the most hostile and rotted-through places, and that many of the devices we use to interpret other people and our environments—received ideas, assumptions, even language itself—are just human inventions that keep us isolated from each other.

2 drexciya (1989-2002). dhalgren is technically a work of science fiction, even as it resembles no work of science fiction i’ve read before. if delany were typing this newsletter, though, he would probably insist that science fiction, at least the good kind, is never exclusively about the future, and is usually more concerned with identifying and exposing the mechanisms that govern the present by offering us a slightly-retuned version of it. (the future is something that hovers beyond those mechanisms. i look forward to maybe getting there someday.) according to this conception, techno is science fiction too. but of course it is. in its very first stirrings it was trying to reimagine the harsh glitter of industrial detroit as spaceship gleam.

from the start, though, drexciya is different. anonymity isn’t an alien concept in dance music, especially among members of the detroit techno collective underground resistance, of which drexciya were a part. but drexciya’s membership remained obscure well into their career, and one half of the group, gerald donald, is still elusive about his involvement. (the other half, james stinson, died in 2002 from a heart condition.)

listening to the music, the people behind it seem almost beside the point. it builds so much of its own world that personalities would just interfere with the fiction’s signal. every drexciya track describes and takes place in invented space, in a black atlantis constructed by the water-breathing offspring of pregnant africans thrown overboard from ships during the atlantic slave trade. it’s a mindbending afrofuturistic narrative that doesn’t just reimagine our current reality but alters the very coursings of past into present. writer greg tate, one of many sources in mike rubin’s invaluable history of drexciya, characterizes the drexciyan mythos as a “revisionist look at the middle passage as a realm of possibility and not annihilation”—from the total despair and dehumanization of slavery and death, life blossoms, and new worlds form.

the music didn’t offer up this mythology immediately. for the first few twelve inches at least, all one had to go on were the track titles (evocative undiscovered geographies like “bubble metropolis,” “aqua worm hole,” and “red hills of lardossa”), allusive sentences in the liner notes, and the odd shape of the music itself. where their contemporaries made music that recalled the evenly-spaced wheezings of mechanical joints, drexciya tracks were more amphibian in nature, built like frogs are, by which i mean they’re stacks of bubbles. percussion boils upward and evaporates. kick drums explode in muffled clouds like depth charges. a synthesizer buzzes and throbs so insistently it feels like you’re caught in the gravity drive of a drexciyan cruiser. i feel like i’ve known the story for so long that my description of the drexciya’s music inevitably comes out drexciyan. but even with the mythology muted in my mind, if i close my eyes and listen, i see crystal structures slowly rising through the ocean floor, schools of tiny watercraft humming between their legs.

in the last two years of drexciya’s activity, stinson planned a series of seven albums he called the “seven storms.” over the course of them, one gets vacuumed out of deep drexciyan waters into our reality (cf. the other people place’s lifestyles of the laptop café, one of the best dance albums of all time) and then vacuumed out of our reality into even more metaphysical and theoretical dimensions (cf. transllusion’s the opening of the cerebral gate, the title of which should be self-explanatory). just thinking about them makes my brain turn inside out like a glove. the final drexciya release, grava 4, found the drexciyans plotting a course from the ocean to their true place of origin, a constellation in deep space. someone uploaded the full album to youtube with its rhythms synced the footage of the apollo program, and i think it’s one of the most thoughtful collisions of sound and image available on the internet. rockets twist through the air; men in space suits float weightlessly over circuit boards; technicians make minor adjustments to hexagons of spacecraft; and drexciya’s music glitters like the stars must have over all of the (in the one bitterly ironic note the video strikes: mostly white) people in the footage: a new world of possibility, just within reach.

3 revolutionary girl utena (1997, j.c. staff, dir. kunihiko ikuhara). last summer when i embarked on the nearly inexhaustible project of rewatching sailor moon—it is 200 episodes long but the quality somersaults so much from arc to arc that it can feel like 400, and time dilates so extremely during the episode where sailor moon’s daughter befriends a dinosaur that i’m pretty sure it is a two day-long event in real time—i noticed the director of my favorite season, sailor moon s (almost perfect, devastatingly gay), kunihiko ikuhara, was also the director of revolutionary girl utena, a show i had previously seen described as “neon genesis evangelion for lesbians.” as a lesbian whose entire adolescence, for better or worse, was shaped by all-night marathon viewings of evangelion, i… had to see this show. right away.

the entire run is on youtube in low quality; i subscribed to funimation’s streaming service to watch it in high quality, which was its own compromised experience (streaming services are bad). i now own the show in two different forms, and have seen it five times. (ugh.) i also recommend trying to find a decent copy of the movie if you can, as together the series and film are the greatest queer work of art i’ve encountered in my life, and the film alone is one of the most overwhelming aesthetic experiences i’ve ever had. watching it is like standing beneath a waterfall of rose petals.

the staging and mise en scené are outrageously stylized. the dueling arena in the tv series is reached by a staircase that spirals upward with an escher-like endlessness. the architecture in the film is even more disjointed, half-constructed art nouveau platforms drifting around like ships without anything to anchor them into space. the camera, freed from the constraints of reality, can move however it wants to, performing 360 degree turns between two characters shadowed in darkness. colored roses spin in the corners of the screen, framing flashbacks or denoting important emotional beats for the characters. in one of my favorite episodes, a pointer indicates every significant object in a room, including the cats gathering in the window.

i would’ve loved the show if it were only as deep as these images; they don’t need anything beneath them to be involving. but utena is about love. the titular character wears a boy’s uniform to school because she wants to become a prince and rescue princesses. she finds herself enmeshed in a series of duels, each of which determines who at her school will possess “the rose bride,” anthy himemiya, and the sword of dios; whoever holds both will gain the ability to “revolutionize the world.” utena participates reluctantly at first, but as her relationship with anthy develops, she finds she wants to protect her from the members of the student council, people who, even if their intentions are noble, would still only use her as a means to an end.

ohtori academy is a middle/high school so of course the student council is made up of emotionally-stunted teens stuck in patterns they desperately want to break out of. they are forever in the position of mistaking something that is not love for love. who among us wouldn’t want to shatter and remake the whole world? but utena and anthy love each other. here look at this gif i found for proof:

anthy isn’t “the rose bride” to utena. she is simply anthy. this small fact allows anthy to finally, tentatively surface from the role she’s been submerged in for centuries, because she’s finally being valued for herself instead of for what can be taken from her. we so often feel like ballerinas under glass, turned by invisible clockwork, seeing a better world beyond but unable to access it. revolutionary girl utena is about shattering that glass, shrugging off every pointless gender role and impossible ideal and fucked-up standard that is imposed on us from without and finding a space outside of that in which to practice love, honesty, and tenderness, without boundaries, world without end. it is the kind of world i believe we have to make.